This article was originally published on April 22, 2016. To read the stories behind other celebrated architecture projects, visit our AD Classics section.

Designed shortly before Zaha Hadid left the Office of Metropolitan Architecture (OMA)—led by Rem Koolhaas—to found her practice, Zaha Hadid Architects, the proposed extension for the Dutch Parliament firmly rejects the notion that imitation is the sincerest form of flattery. Rather than mimic the style of the existing historic buildings, OMA elected to pay tribute to the complex’s accretive construction by inserting a collection of visibly postmodern, geometric elements. These new buildings, unapologetic products of the late 1970s, would have served as unmistakable indicators of the passage of time, creating a graphic reminder of the Parliament’s long history.

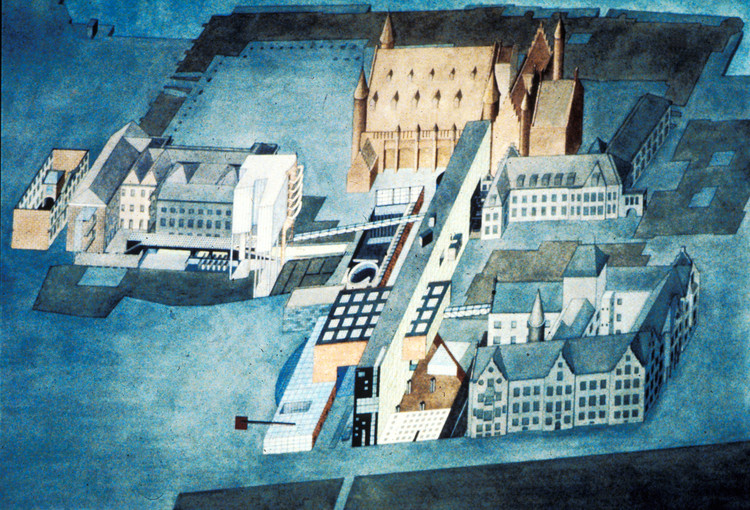

The complex that houses the Dutch Parliament, known as the Binnenhof, is situated in the heart of The Hague – The Netherland’s governmental capital. The oldest structures in the Binnenhof were built in the 13th century, with several additions made as the complex adapted to serve a variety of programs – from a royal palace to the headquarters of the fledgling Dutch Republic. The center of the complex was dominated by the Ridderzaal (or Hall of Knights), a Gothic structure that received a Romantic restoration in the 19th century. By then, the Binnenhof had finally settled into its current role as the meeting place of the Dutch Parliament, and had become an agglomeration of buildings representing six hundred years of shifting architectural styles.[1]

When a competition for a new extension of the Binnenhof was announced in 1978, there was more at stake than the creation of new office space. The competition brief called for a deeper reinterpretation of the complex, one which would physically—and symbolically—separate the gathering spaces of the Parliament from the office spaces of the government proper.[2] The new Parliament buildings were to stand on a roughly triangular site just beyond the rectangle formed by the original medieval fortress.[3]

OMA’s proposal consisted of three main elements, the products of three different designers: Zaha Hadid, Elias Zenghelis, and Rem Koolhaas. Hadid proposed a long, tall, and narrow rectangular office block, parallel to a lower, wider block designed by Zenghelis. The two orthogonal elements stood in contrast to Koolhaas’ contribution, an extrusion of an irregular plan sitting atop pilotis. Though connected by bridges, the three structures were otherwise spatially independent of one another.[4]

The main point of incorporating public access in the proposed addition was in the horizontal block designed by Zenghelis. Facing directly onto an open plaza, this structure—built of glass bricks—was to be the main forum for political activity; accordingly, it would house a number of meeting rooms of various sizes for varying purposes. Toward the northern end of the block was an elliptical tower whose ovoid rooms were connected by a spiraling ramp. The tower’s mezzanine would serve as a space for the press – those who would serve as representatives for the Dutch public.[5] Going beyond the specified distinction between government and Parliament, this added layer of separation between government and the public increased the number of factions to be represented in the Binnenhof to three.

Running parallel to Zenghelis’ public forum was the tall, narrow volume of Hadid’s Parliament block. Whereas the lower structure was to be open to the public, its loftier neighbor was reserved for the business of politicians.[6] The upper levels of the building provided space for political parties to gather and discuss their positions, while the lower levels were to accommodate the professional managers of parliamentary procedure. The two groups could then move toward the center of the building, where an ambulatory led them into the assembly room itself.[7] Office space for the members of Parliament and their staff were to remain in the existing structures in the complex, where proposed arcades would lead from three courtyards to the assembly hall.[8]

The assembly room was not fully contained within either Zenghelis’ or Hadid’s building elements. Instead, it rose straight up from the roof of the public block, then bent to a horizontal thrust that pierced through the Parliament block. This connectivity carried clear symbolic intention: in essence, the assembly room was intended as a bridge between the amateur and the professional, the civilian and the government. The overhang of the assembly also served as a new gateway to the interior of the Binnenhof, framing a view of the Ridderzaal within.[9]

Almost entirely detached from the other two additions, Koolhaas’ contribution literally towered over both. Its form was an extrusion of an irregular polygonal plan.[10] Though seven stories tall, the tower only contained five habitable levels which sat upon a number of two-story high pilotis.[11] It was from beneath this tower, between the small forest of pilotis, that the long, trussed ramp led from the Parliamentary offices to the assembly hall itself.[12]

The end result of the collaboration between Hadid, Zenghelis, and Koolhaas did more than simply address the programmatic and symbolic directives laid out in the brief. The trio of late 20th century buildings, while visually quite distinct from their older neighbors, were by no means out of place. In fact, their stark modernity was meant to respect what OMA deemed the “slow-motion process of transformation” that had led to the Binnenhof’s eclectic representation of Dutch architectural epochs.[13] Though it was ultimately never realised, OMA’s proposal remains a fascinating glimpse of what could have been, and raises the question of how the Binnenhof will continue to transform in the future.

References

[1] "Dutch Parliament Extension." OMA. Accessed April 18, 2016. [access]

[2] Fabrizi, Mariabruna. "Applying the Cadavre Exquis: The Competition for the Dutch Parliament Extension, OMA (Koolhaas, Zenghelis, Zaha Hadid) – 1978." Socks. November 22, 2013. [access]

[3] Futagawa, Yukio, ed. GA Architect: Zaha M. Hadid. Tokyo: A.D.A. EDITA Tokyo, 1986. p38.

[4] Fabrizi.

[5] Futagawa, p39.

[6] “Dutch Parliament Extension.”

[7] Futagawa, p39.

[8] “Dutch Parliament Extension.”

[9] Futagawa, p39.

[10] Fabrizi.

[11] Futagawa, p38.

[12] “Dutch Parliament Extension.”

[13] Fabrizi.